By: Kenneth Cutler

Published in the Florida Supreme Court Historical Review Magazine Historical Review Fall/Winter 2021 Edition

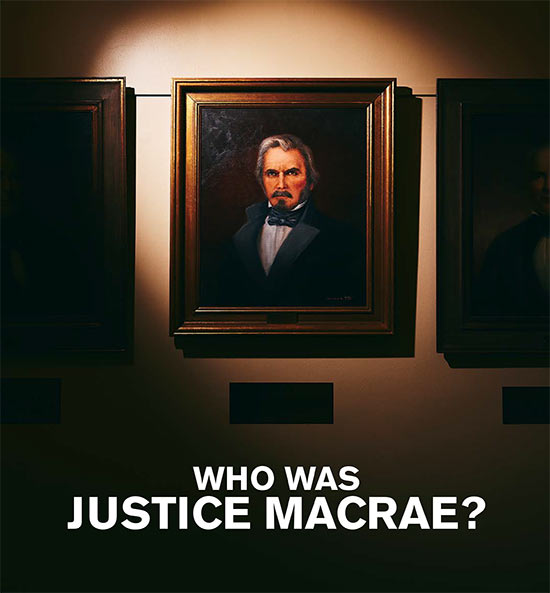

At the stately Florida Supreme Court building located on South Duval Street in Tallahassee, portraits of all former justices of the Court hang on the inner and outer walls of the courtroom. This portrait gallery is the largest and most historically significant body of art in the building. The Court was established in 1846, shortly after Florida’s entry into statehood, a time when the new age of photography was in its infancy, and some of the portraits are said to be the only existing likenesses of the justices.

Unbelievably, as prominent and historically important as these individuals are, one of the portraits is an absolutely fictional representation, and – until now – the story of the jurist in the painting, Justice George W. Macrae, one of the Court’s earliest members, has been shrouded in mystery.

The Court website contains summary reference biographies for all the justices. Macrae’s brief biography states:

“Former Justice George Macrae is the fourth Supreme Court Justice and is one of the mysteries of the Court. Little information has been uncovered about him. He served for one year, 1847. [The] painting . . . of the justice is entirely imaginary. No actual photograph or portrait of him has ever been identified. There is no evidence of the date and place of his birth or of his family history. Macrae first came into prominence in Florida in 1842, when President John Tyler appointed him United States Attorney for the Southern District. Two years later, Macrae won election to the territorial senate from South Florida. When another candidate declined appointment in 1847 as circuit judge for the southern circuit, Governor William Moseley turned to Macrae, whom the legislature had also previously considered for the position. After serving only a single year as circuit judge/Supreme Court justice, Macrae was replaced by Florida House of Representatives Speaker Joseph Lancaster. Macrae’s activities after leaving the court are as uncertain as his origins.”

The portrait described above was painted by Claribel B. Jett and commissioned by Chief Justice Joseph A. Boyd, Jr., in 1984 to fill in the gaps in the justices portrait collection, which was lacking Justices Macrae, Ossian B. Hart, Franklin D. Fraser, and Albert G. Semmes. In a “tweet” published by The Florida Bar on January 4, 2018, Jett is described as operating a portrait studio in Tallahassee from 1962 to 1974 and is purported to have used photographs of Macrae’s descendants to create the portrait likeness. This is contradicted by Erik T. Robinson, Archivist at the Supreme Court of Florida Library, whose vivid recollection was that he had been working as a curator at the Museum of Florida History, across the street from the Florida Supreme Court, when Claribel Jett came to the Florida Supreme Court Building to add her name to the painted portraits in the lower right corner of each of the four that she had created in 1984, when Chief Justice Joseph Boyd commissioned the portraits.

“The portraits she created did not have an artist’s signature until then, years after they were painted and put on display at the court” Robinson said. “She spoke to me about the Macrae portrait while she was in the act of painting her name on the justice portrait. Again, I did not record the conversation, so my memory of the event is all I can contribute. What I remember her saying was that she had never found any information about or image of him, so she started by painting ‘an uncle’ of hers and dressed the resulting figure in a fanciful costume. (I note that the clothing worn by the “Macrae” figure is not historically accurate.) Ms. Jett was quite elderly and physically infirm. She had the help of another older woman named Iona Skuce, who handed her the tiny brush and held her elbow while Ms. Jett added her signature to each of the four paintings, Ms. Skuce reloading the brush with white paint frequently. I note that several of the signatures are now darkened to an off-white and the paint used may not have been artist’s oil paint or acrylic paint.”

An attempt to resolve this mystery first brings one to the book The Supreme Court of Florida and Its Predecessor Courts, 1821-1917, which also describes the justice as an enigma. Its brief history of Macrae begins, “If mystery surrounds the life of any member of Florida’s supreme court, that individual is George W. Macrae,” and concludes: “Macrae’s activities after stepping down from the court are as uncertain as are his origins.”

New, extensive research into the elusive justice leads to the conclusion that Justice George W. Macrae was George Wallace Macrae, son of John and Elizabeth (Wallace) Macrae of Prince William County, Virginia, and that he was born in that county on June 24, 1802; died in Kentucky on March 6, 1858, at the age of 55; and is buried in the Dade Family Cemetery at Church Hill, Christian County, Kentucky.

Macrae’s family roots go back several generations in Virginia and he and his family members were slaveholders or certainly benefitted from the labor of slaves. Documents show both his father, John, and his grandfather Allan Macrae as land (and slave) owners in the area of Dumfries, Virginia. The father owned acres of Virginia land and there are references to either him or George W. Macrae’s brother John in numerous Prince William County newspapers of the time.

An 1828 news article concerning the death of Colonel Barnaby Cannon, a fellow member of the Prince William County Bar, confirms George Macrae’s middle name to be Wallace, the import of which ties in with the death records found in Kentucky and on his tombstone, both of which indicate his middle name to be “Wallace”. It is also the maiden name of his mother, Elizabeth Westwood Wallace.

Several letters that were reproduced in text by Ronald Ray Turner on the website “pwcvirginia.com”, and transcribed from archival records suggest that George W. Macrae was an attorney practicing as early as 1823 in the county and specifically Brentsville, the county seat of the time. His brothers James W. Macrae and John Macrae were also attorneys in Prince William County. George W. Macrae was advertising his services as an attorney at law in local papers in 1824, serving Superior and Inferior Courts of Loudoun, Prince William, and Fairfax Counties, Virginia, and in the Fredericksburg District. According to the advertisements, his office was in Brentsville.

Macrae’s legal practice was varied, often involving property and trust work as well as criminal cases. In 1836, he served as a court-appointed defense attorney for a slave who was accused of assault and eventually convicted and sentenced to hang.

He was extremely active in local politics and frequently represented Prince William County before the Virginia General Assembly. For example, at a meeting of county freeholders on May 26, 1825, Macrae was elected as one of six delegates to represent the county at a state meeting concerning constitutional amendments to be held in August that year at Staunton, Virginia. In July 1826, Macrae, along with several other Prince William County citizens — including John Macrae, John W. Tyler (a relative of the future President), and William A.G. Dade — were appointed as part of a committee to assist in the receipt of funds to aid former President Thomas Jefferson in the discharge of his debts. (This and other associations with Dade, a judge of the General Court of Prince William County, may be a family connection that helps explain Macrae’s burial in the Dade Family Cemetery in Kentucky. )

An article in 1839 suggests that Macrae was a Captain in the Virginia Militia and that he was appointed as a Prince William County delegate to the Democratic Party state convention in

Richmond that year. In 1840, a hint that he might have been tapped as a candidate to represent the county in the General Assembly comes in the form of a published declination on his part.

The tumultuous politics of the times, and the death of President William Henry Harrison one month into his term, may have been fortuitous for Macrae, because his fellow Virginian, Vice President John Tyler, assumed the Presidency on April 4, 1841. Macrae presided in January 1842 over a county Democratic meeting where he also was named a delegate to the statewide party convention in February. By August, newspapers were reporting his appointment by President Tyler to the post of United States Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, after L.W. Smith resigned from the position. Macrae seems to have assumed the post and arrived in Florida by the end of 1842.

After two years as U.S. Attorney, he was elected to represent South Florida in the Florida Territorial Senate. One reference suggests he was the last president of that Senate, in 1845, the year Florida was admitted into the Union. Among Macrae’s actions as Senate president, he executed a resolution seeking to gain statehood for Florida as a slave-holding state, to counterbalance the admission of Iowa as a non-slave state.

In the new state, justice was administered by circuit-riding judges and, in 1846, Macrae became the judge for the Southern Circuit, which included vast Monroe County. This appointment as the Southern Circuit judge continued when he was named to the Florida Supreme Court bench for a single year’s term in 1847.

The Florida Supreme Court Minute Book, kept in the Court archives, lists Macrae as being present at the Court throughout its two-month session from early January to early March 1847 and again on January 3, 1848; but on January 7, 1848, his successor, Joseph B. Lancaster, took his place. During his time on the Court, Macrae appears to have authored five cases opinions, all issued in January 1847.

That summer, a Tallahassee newspaper reported on June 26 that Macrae had returned to the capital city – apparently from Key West — aboard the U.S. Schooner On-ka-hy-ee. He continued to ride circuit through the end of the year. On December 11, 1847, Macrae heard a Hillsborough County divorce case, Parish v. Parish, also in the Southern Circuit. He then headed north to preside on December 19 over the Chancery case of Lynch v. Cole et al. in a Marion County court, part of the state’s Eastern Circuit. After that, he moved swiftly to Columbia County, where on December 21 he was on the bench for Mattair v. Jones, an estate dispute.

While a judge, Macrae was very active in Florida Freemasonry, and multiple sources refer to his many different leadership roles in the organization. For example, during the two months he was sitting on the Supreme Court, he attended a meeting of the Grand Royal Arch Masons Chapter in Tallahassee on Thursday evening, January 21, 1847, where he was installed as Grand Scribe. Masonic records also document his continued presence in Florida for a time after he left the judiciary: A note of proceedings held at the Grand Lodge of Florida (Freemasons) in Tallahassee on January 8-10, 1849, shows him in attendance as a member of Dade Lodge No. 14 and “District Deputy Grand Master for the Southern District of Florida.” After that, we find no more references to Macrae in Florida.

But, on May 21, 1849, a “Judge Geo. W. Macrae” is found in New York, boarding the bark (sailing ship) Alice Tarltan for California. The San Francisco City Directory of September 1, 1850, lists Geo. W. Macrae, counsellor, on Clay Street between M and Kear. The book California Imprints, (August 1846-June 1851) confirms this to be our Macrae, indicating that, in 1850, a man by the same name had a brief venture with Washington Bartlett in publishing a newspaper called the Journal of Commerce and Daily Bulletin. The book further states, “Bartlett brought the press from Florida, and Macrae was also from Florida, having been a judge of the supreme court there.” In the same year, Macrae attended the first legislative session of the new State of California, where he was nominated and ran for chief justice of the Superior Court of San Francisco; he came in second in the voting and was thereby not appointed.

He returned to involvement in Masonry, and held a leadership role in 1850 as a founding member of Madison Lodge No. 23, located in Grass Valley, California. He apparently was a member just in 1853, as his name disappears from lodge rosters in later years. Macrae also served as an officer in a California division of the Sons of Temperance, as noted in an 1851 article in The New York Times. In 1854 he opened a firm with Augustus Heslep, Heslep & Macrae, on the corner of Merchant and Montgomery Streets in San Francisco. By 1856, he appears at a different location from Heslep in the City Directories, so it is assumed the partnership had broken up. The last reference found of him in San Francisco is in the 1858 City Directory, at 101 Merchant Street. Searches in the same directory for 1859 through 1865 yield no results for George W. Macrae. No death records, obituaries, or notices of his death are found in California searches.

Death records in Christian County, Kentucky, may reveal the answer of where George W. Macrae went. There, recorded for March 6, 1858, “Geo. W. Macrae” died of dysentery at the age of 54, near the community of Lindsay’s Mill. He is listed as single, born in Virginia, and his occupation is “Lawyer.” His parents are listed as John and Elizabeth Macrae. He is buried at Dade Family Cemetery. The gravestone marker clearly indicates that Geo. Wallace Macrae is buried there. The Find-A-Grave memorial listing for this burial indicates his birthplace as Prince William County, Virginia, bringing us full circle with the George W. Macrae described earlier.

We also can assume that the George W. Macrae buried in the Dade Family Cemetery is in fact the former Florida Supreme Court justice because of another grave in the same cemetery: that of Charles Lucien Dade, who was born August 8, 1813, in Virginia and died August 3, 1854, in Christian County, Kentucky. The will of a Lucien Dade, found in Christian County probate records and dated July 19, 1853, mentions that Lucien’s son was named William A.G. Dade, presumably the namesake of the judge connected early on to George W. Macrae in Prince William County, Virginia. Furthermore, the will specifically mentions members of both Wallace and Macrae families.

Several connections with a man named Lucien Dade had been documented during Macrae’s Virginia days. A Lucien Dade served as prosecutor when Macrae defended a slave on capital charges of assault. Presumably the same Lucien Dade was named along with Macrae as a delegate to the February 1842 Virginia Democratic convention. Lastly, the 1840 Federal Census for Prince William, Eastern District, Virginia, actually has Geo. W. Macrae and Lucien Dade on the very same page, clearly indicating that they were neighbors. Contact has been made with members of the Dade family of Christian County, Kentucky, in the hopes of finding additional records.

This research also may have brought us closer to knowing what Justice Macrae might truly have looked like. The website “ancestry.com” has several family trees with the Macrae family and several photos of family members, including George W. Macrae’s brother Bailey Macrae. Additionally, members of the Dade family in Christian County, Kentucky, have provided the author with a daguerreotype photograph of Macrae’s sister, Amelia Ann “Emily” Macrae.

While further extensive verification with documentation and other records, potentially including those from the Dade Family Cemetery, would solidify this theory further, it is believed that this Geo. Wallace Macrae is the mysterious George W. Macrae, the Florida Supreme Court justice for whom so little had been previously known. The evidence trail presented here certainly suggests that conclusion.

References Used:

1. Cornell Law School. Respondeat Superior | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute (cornell.edu). Accessed November 3, 2021.

A photo of the official Court portrait of Justice Macrae accompanies his online biography, which can be found at the Court’s website. Justice George W. Macrae, FLA. SUP. CT. (last modified Dec. 19, 2018), https://www.floridasupremecourt.org/Justices/Former-Justices/Justice-George-W.-Macrae.

2. E-mail from Craig Waters, Director, Pub. Info. Off., Fla. Sup. Ct., to author (June 21, 2021) (on file with author).

3. @TheFlaBar, TWITTER (Jan. 4 2018), https://twitter.com/TheFlaBar/status/949058652232560640.

4. E-mails from Erik T. Robinson, Archivist, Sup. Ct. of Fla. Lib., to author (June 21 & 22, 2021) (on file with author).

5. MANLEY ET AL., THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA AND ITS PREDECESSOR COURTS, 1821-1917 127-28 (Walter W. Manley II, E. Cantor Brown, Jr. & Eric W. Rise, eds., Univ. Press of Fla. 1997).

6. Steve Nass, George Wallace Macrae, FIND A GRAVE (June 21, 2014), https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/131674216/george-wallace-macrae.

7. Guide to African American Manuscripts, VA. HIST. SOC’Y, https://virginiahistory.org/sites/default/files/uploads/AAG.pdf (1831 bond of George W. Macrae covering the hire of the slave Clary and her child from James Fewell).

8. The grandfather’s first name is spelled both “Allan” and “Allen” in various documents and publications of the time. See, e.g., Image 1 of George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Allan MacRae to George Washington (May 13, 1755), LIBR. OF CONGRESS, https://loc.gov/resource/mgw4.029_0223_0225/?st=text (a 1755 letter from the grandfather to George Washington uses “Allan”). But see, e.g., FAUQUIER HISTORICAL SOCIETY, BULLITIN 371 (4th ed. 1924) (a 1759 deed of property conveyed to the grandfather uses “Allen”).

9. Guide to African American Manuscripts, supra note 7; see Virginia census records of the time.

10. James Fewell & Thos. R. Hamilton, Constitutional Whig, Pleasants & Smith (Aug. 23, 1823), at 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045110/1828-08-23/ed-1/seq-3/.

11. Multiple family tree references to the marriage between John Macrae and Elizabeth (Eliza) Westwood Wallace on September 11, 1788. See All Family Trees results for John Macrae, ANCESTRY (last visited Oct. 20, 2021), https://www.ancestry.com/search/categories/42/?name=john+_macrae&event=_prince+william-virginia-usa_2440&count=50&defaultFacets=PRIMARY_YEAR.PRIMARY_NPLACE&event_x=_1-0&location=2&name_x=s_s&priority=usa.

12. James Pleasants Jr. Esq., Virginia Governors Executive Papers (Nov. 24, 1823), http://www.pwcvirginia.com/documents/JamesPleasantsJr.pdf (Letter from George W. Macrae, Brentsville, Va., Box #6, Folder 3, Accession # 42046 Commonwealth vs Burgess). Here, Macrae writes to the General Court about a murder trial in which he represented the accused. There are subsequent letters concerning this representation and matter at the same cite. See HENRY HOWE, HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS OF VIRGINIA 5 (Charleston, S.C.: W.R. Babcock 1847).

13. Ronald Ray Turner, Prince William County Virginia, https://www.pwcvirginia.com/ (last visited Oct. 20, 2021).

14. See https://www.fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html Washington DC National Intelligencer 1823-1825 – 0471.pdf.

15. See, e.g., Decrees for Sale of Land, Phenix Gazette, [volume], (Alexandria, [D.C.]), (June 22, 1833), in Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025006/1833-06-22/ed-1/seq-3/.

16. See Turner, supra note 13.

17. Joan W. Peters, Slave & Free Negro Records from the Prince William County Court Minute & Order Books: 1752-1763; 1766-1769; 1804-1806[;] 1812-1814; 1833-1865 (Broad Run, Va.: Albemarle Research, 1996), https://eservice.pwcgov.org/library/digitallibrary/PDF/PWC%20Slave%20&%20Free%20Negro%20Records%201752-1865.pdf.

18. Prince William Proceedings, Phenix Gazette [volume] (Alexandria [D.C.]) (May 26, 1825), in Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025006/1825-05-26/ed-1/seq-2/.

19. Scott Harp, John William Tyler, HISTORY OF THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT (2001), https://www.therestorationmovement.com/_states/illinois/tyler.htm.

20. Miscellaneous, Richmond Enquirer [volume] (Richmond, Va.) (Aug. 22, 1826), in Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024735/1826-08-22/ed-1/seq-4/.

21. See Daily Richmond Whig, [volume], (Richmond, Va.) (Nov. 13, 1829), in Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85026767/1829-11-13/ed-1/seq-2/.

22. Alexandria Gazette [volume] (Alexandria, D.C.), (March 12, 1839), in Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1839-03-12/ed-1/seq-2/.

23. Alexandria Gazette [volume] (Alexandria, D.C.) (March 11, 1840), in Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1840-03-11/ed-1/seq-3/.

24. John Tyler: The 10th President of the United States, WHITE HOUSE, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/john-tyler/ (last visited Oct. 20, 2021).

25. Meeting in Prince William County, RICHMOND ENQUIRER (Feb. 1, 1842).

26. Reported in multiple newspaper sources of the time. See The Madisonian [volume] (Washington City [i.e. Washington, D.C.]) (Aug. 30, 1842), in Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015015/1842-08-30/ed-1/seq-1/; see also The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Md.),(Aug. 29, 1842), p.4; Journal of the executive proceedings of the Senate … [vol. 6], 1841-1845, at 115, EXECUTIVE J. (July 21, 1842), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435066736042&view=1up&seq=119&q1=macrae.

27. Perhaps in preparation for his departure for Florida, Macrae, in consideration for $20, granted a parcel of land to his brother B. (Bailey) Washington Macrae. The land, part of a tract George W. Macrae had inherited from his father, was the site of the Macrae family graveyard. The indenture is purported to have been made on September 30, 1842, and was acknowledged in the Clerk’s Office of the Prince William County Court on October 15, 1842, by George W. Macrae as attested to by one J. Williams Court. Deed (Oct. 15, 1842), https://www.pwcvirginia.com/documents/1ORANGE-FIELD.pdf.

28. MANLEY ET AL., supra note 5, at 127.

29. https://www.morphyauctions.com/jamesdjulia/item/2040-398/.

30. Res. of the Gov. & Legis. Co., item 51 (Fla., Jan 27, 1845).

31. JEFFERSON BEALE BROWNE, KEY WEST: THE OLD AND THE NEW (St. Augustine: The Record Co. 1912).

32. Joseph A. Boyd, Jr. & Randall Reder, A History of the Florida Supreme Court, 35 U. MIAMI L. REV. 1019, 1023 (1981), https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol35/iss5/7.

33. E-mail from Erik T. Robinson, Archivist, Fla. Sup. Ct. Lib., to author (June 28, 2021) (on file with author). Lancaster had been Speaker of the Florida House of Representatives when he was elected to the Court by the Legislature in December 1847. See Manley et al., supra note 5, at 128.

34. Bennett v. Filyaw, 1 Fla. 403 (Jan. 1847); Dorman v. Bigelow, 1 Fla. 281 (Jan. 1847); Horn v. Gartman, 1 Fla. 197 (Jan. 1847); Raney v. Baron, 1 Fla. 327 (Jan. 1847); Wood v. Bank of State, 1 Fla. 378 (Jan. 1847).

35. The Floridian (Tallahassee, Fla.) (June 26, 1847), https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00079927/00502/2x?search=g.w.+macrae.

36. The News (Jacksonville, Fla.) (Dec. 31, 1847).

37. Ocala Argus (Ocala, Fla.) (March 25, 1848), https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00048641/00003/7x?search=geo.+w.+macrae.

38. J. COCKROFT, ENCYCLOPEDIA OF FORMS AND PRECEDENTS FOR PLEADING AND PRACTICE AT COMMON LAW, IN EQUITY, AND UNDER THE VARIOUS CODES AND PRACTICE ACTS (1900), https://www.google.com/books/edition/Encyclopaedia_of_Forms_and_Precedents_fo/Fzg1AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

39. See, e.g., https://www.masoniclib.com/images/images0/553353422728.pdf.

40. Proceedings of the Organizing Convention (1847 & 1848), https://flgyr.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Grand_Chapter_RAM-18471848.pdf.

41. M.W. THOMAS BROWN, GRAND MASTER, PROCEEDINGS OF THE GRAND LODGE OF FLORIDA (Jan, 8, 1849), https://www.google.com/books/edition/Proceedings_of_the_Grand_Lodge/yV9HAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22george+w.+macrae%22&pg=PA255&printsec=frontcover.

42. CHARLES WARREN HASKINS, THE ARGONAUTS OF CALIFORNIA: BEING THE REMINISCENCES OF SCENES AND INCIDENTS THAT OCCURRED IN CALIFORNIA IN EARLY MINING DAYS 449 (Fords, Howard & Hulbert 1890), https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Argonauts_of_California/-M4BAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=macrae.

43. United States City and Business Directories, ca. 1749 – ca. 1990. p.74, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DB-26HQ?cc=3754697.

44. Henry Raup Wagner, California Imprints (Aug. 1846-June 1851). United States, n.p, 1922, p.49.

45. The Buffalo Weekly Republic (Buffalo, N.Y.) NEWSPAPERS.COM (June 4, 1850), p.5,

https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=13776075&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI1NDUyODY2MiwiaWF0IjoxNjIzOTU3MTk2LCJleHAiOjE2MjQwNDM1OTZ9.pdh1NVRKWsrwvEtnVgliRP4PBkiEX-K-P-VPW6jY_g4; see also Journal of the Senate of the State of California at their First Session Begun and held at Puebla De San Jose, on the Fifteenth Day of December 1849, session notes for April 5, 1850, pp. 282-284, https://archive.org/details/jourofl00cali/page/n7/mode/2up?q=macrae.

46. Freemasons, Grand Lodge of California, Proceedings of the M. W. Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of California, at the … annual communication 226-28, 254, 268-69. (San Francisco, Cal.: The Lodge 1850), https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofmwg185054fre/page/228/mode/2up?q=macrae.

47. E-mail from Joe Evans, Archivist and Museum Collections Manager, Henry W. Coil Lib. & Museum of Freemasonry, Masons of Cal, to author (June 22, 2021) (on file with author) (“We have very little documentation on members or Masonic lodges prior to 1906 as the majority of records for the Grand Lodge of California were destroyed as a result of the earthquake and fire of 1906. The 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed most of the historical records of institutions in San Francisco which renders research of individuals in San Francisco in the 19th century very difficult. However, from the bit of records we do have, it seems that George W. Macrae was a founding member of Madison Lodge No. 23, located in Grass Valley, California. He seems to have been a member for only the year 1853 as his name drops off the rosters for the lodge in subsequent years.”)

48. The New York Times (New York, N.Y.) (Nov. 18, 1851), p.3, https://www.fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html.

49. Advertisement, SAN FRANCISCO EVENING J. (online) (Apr. 12, 1854), https://infoweb.newsbank.com.

50. Harris, Bogardus, & Labatt, San Francisco City Directory for the Year Commencing October, 1856, ARCHIVE.ORG,

https://archive.org/details/sanfranciscocity1856harr/page/n15/mode/2up?q=macrae.

51. Henry G. Langley, The San Francisco City Directory for the Year 1858, ARCHIVE.ORG, https://archive.org/details/sanfranciscodire1858lang/page/8/mode/2up?q=macrae.

52. This age conflicts with the age 55 that can be derived from birth and death dates on Macrae’s tombstone. See supra note 7. Christian County, Kentucky, death records for Macrae do not include a date of birth, but all other references are consistent.

53. Ancestry.com. Kentucky, U.S., Death Records, 1852-1965 [database on-line]. Lehi, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2007, https://search.ancestry.com/cgibin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=1222&h=471639&tid=174179302&pid=322267330792&queryId=4722263b1900f2349d83010be6bb6a10&usePUB=true&_phsrc=qmg314&_phstart=successSource.

54. Nass, supra note 6.

55. Charles Lucien Dade, FIND A GRAVE (June 21, 2014), https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/131669893/charles-lucien-dade.

56. Kentucky Probate Records, 1727-1990, database with images, FAMILYSEARCH, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9P32-9B32?cc=1875188&wc=37RR-7MQ%3A173387801%2C174073401 (May 20, 2014), Christian Will records, Index, 1854-1856, Vol. P > image 72 of 472; county courthouses, Kentucky.

57. Peters, supra note 17.

58. Meeting in Prince William County, supra note 25.

59. Year: 1840; Census Place: Eastern District, Prince William, Virginia; Roll: 574; Page: 294; Family History Library Film: 0029691.

60. Thus far, no photographs, portraits, or sketches of George W. Macrae have been uncovered, but he was a man of great early significance, and it is believed that there must be something out there.

61. E-mail from Elizabeth Allingham, Dade Family Cemetery trustee, to author, with a daguerreotype photograph attached (July 22, 2021) (on file with author).